In this article, we examine the backside Salad grind.

Once you understand how to lock in properly, this trick becomes remarkably stable. You can sit back and grind for as long as your speed allows.

I personally enjoy this trick on a ramp, although it works on a ledge as well. Here, we focus specifically on the Salad grind on transition. If you would like an article dedicated to the ledge version, please feel free to let me know in the comments.

Summary

Push your board to lock in

Adjust the strength of your pump and the force with which you push your board, allowing it to slide slightly along the transition surface before locking in. This forward-pushing motion also helps you maintain momentum against friction after the lock-in.

Stay inside the ramp

Keep your body positioned inside the ramp and direct your board firmly toward the coping.

Keep your shoulders open when locking in

Keeping your shoulders open allows you to anticipate your exit trajectory without needing to look directly.

Simulation

Press the icon to launch the 3D simulation.

Definition of Salad Grind

Let us begin with the definition

The backside Salad grind is performed by locking the rear truck onto the obstacle while the front truck is twisted backward.

Some may view this as merely a crooked variation of a 5-0 grind, and that perspective is understandable.

In fact, a Salad grind can sometimes resemble a misaligned 5-0. If you prefer to categorize it as a 5-0, that is entirely acceptable.

How Salad grind differs from a 5-0 grind

Despite what some riders claim, I believe the Salad grind is distinctly different from a standard 5-0.

One of the reasons I refer to it as the Salad grind rather than a 5-0 is that it possesses characteristics that the classic 5-0 simply does not.

Features of Salad Grind

Feature #1 The tail dips lower

In a Salad grind, the tail can dip below the level of the coping.

By rotating the board backside, the tail gains clearance, allowing it to move lower without making contact with the ledge or coping.

Feature #2 The heelside wheel carries your weight

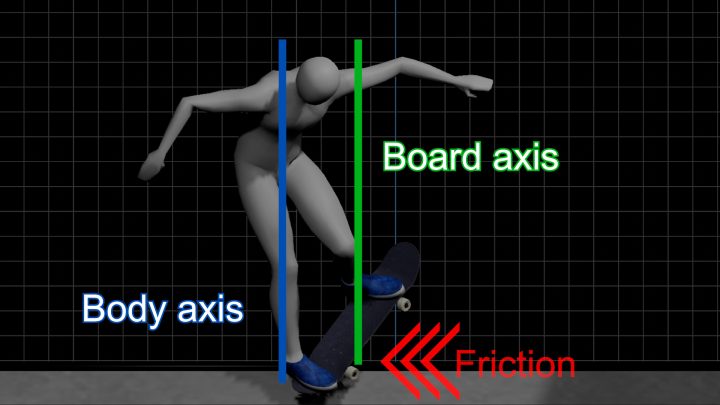

Unlike the 5-0 grind, where the rear truck as a whole supports your weight, in a Salad grind most of your weight shifts onto the heelside wheel of the rear truck.

Physics of Salad Grind 1

Force #1 Gravitational force

Gravity always pulls your body downward toward the ground, regardless of whether you are skating a ramp or a ledge.

To place the heelside wheel onto the coping, you must first pump and help your board rise to the coping level.

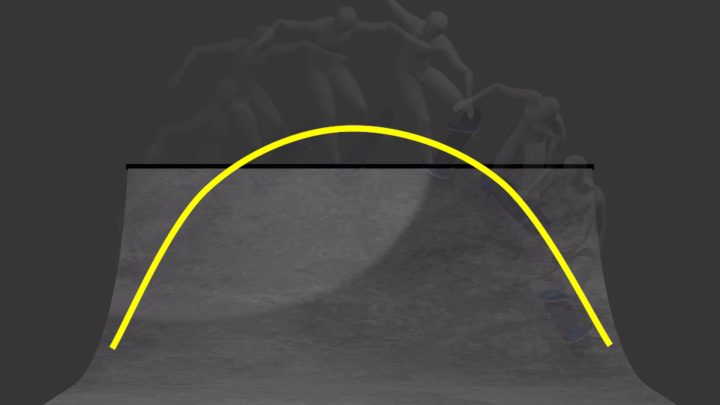

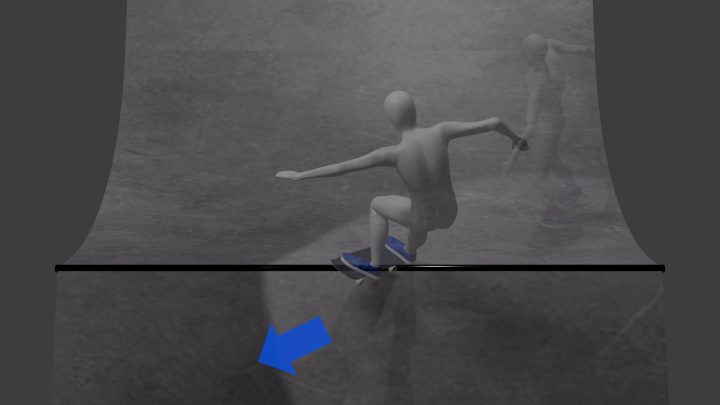

Viewed horizontally, your movement follows a parabolic arc. If the peak of that arc rises above the coping, you will overshoot and land on the deck. This is similar to throwing a ball toward the transition: if the ball has too much upward energy, it ends up on the deck.

There are ways to prevent this overshoot—which we will discuss shortly—but the principle remains: the upward component of your motion should not be excessive.

In other words, you need enough energy to climb the transition, but your vertical momentum must diminish by the time you reach the coping.

Physics of Salad Grind 2

Force #2 Horizontal force

Let us now examine the motion from a top-down perspective.

Whether you are skating a ramp or a ledge, the idea is the same: you approach the obstacle at a certain angle.

If you do nothing, the horizontal momentum carries through the lock-in, causing you to travel straight onto the deck or the top surface of the obstacle.

To prevent this, pump your body toward the bottom side of the ramp and stay inside the ramp. The intensity of this pump should correspond to your speed and the steepness of the transition.

Physics of Salad Grind 3

Force #3 Friction

During the grind, you constantly receive friction from the obstacle. To continue moving, you must place your weight behind the board to push it forward through that friction.

In this respect, the Salad grind resembles a powerslide: you keep substantial weight over the rear and drive the board forward against the resisting force.

Because you must push the board forward, timing is essential.

You should begin this forward-pushing motion slightly before reaching the coping, while still maintaining your body inside the ramp.

The sensation is similar to performing a powerslide on transition: place substantial weight on the heelside and allow the board to slide momentarily before locking in.

I also recommend keeping your shoulders open during the lock-in.

This orientation helps you face the direction of travel, making it easier to guide your momentum parallel to the obstacle.

In practice, my upper body is already oriented forward before I lock in. Although my eyes focus on the rear truck at the moment of contact, because my face is already turned forward, I can still perceive the exit path in my peripheral vision. This greatly assists in determining the appropriate degree of inward lean and the adjustments needed for a controlled grind.

Convert your video into 3D

Convert your video into 3D Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter